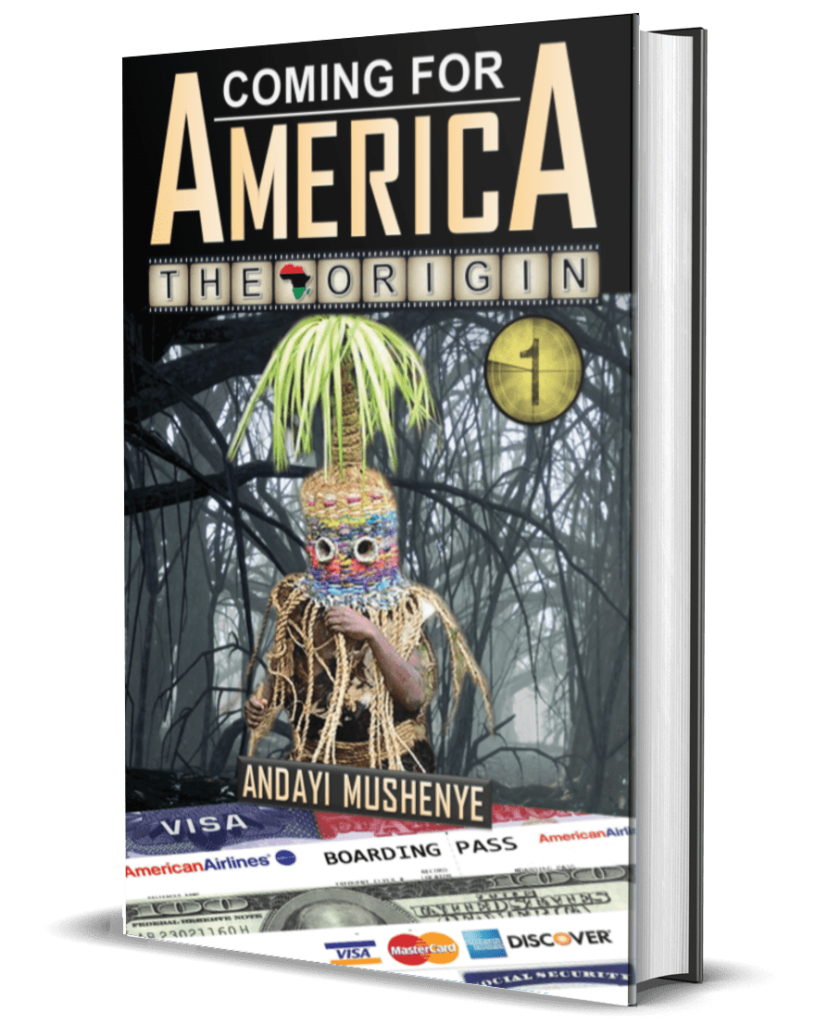

BOOK SUMMARY

About a year after clinging to life and surviving a traumatic uvulectomy and tonsillectomy, a young and impatient.

Andayi Mushenye, a member of the Tiriki subtribe, an offshoot of the Luhya tribe in western Kenya, escapes home to undergo the rite of passage to manhood. The minute he survives an imminent udder attack, he is captured and frog-marched into the ancestral forest,

where he is circumcised without any anesthesia. Before the hemorrhaging stops, Andayi and others in the new cohort of boys-to-men are immediately hauled off to live in an intensely

secluded hut.

Throughout the indigenous stint, the initiates face frightening flare-ups and daunting excursions. Finally, after overcoming arduous challenges, the troopers are officially inducted into manhood with the biggest celebration of their life.

However, his newly-found status flounders when he suffers failure, humiliation, and rejection but gets a job earning forty dollars a month. On this budget, he sets his eyes on America: the paradise on earth where he believes its people lavish in free-flowing milk and honey.

But flat broke and stuck in the village in Africa, there is no chance in a million. Yet, with craftiness, cunning, and unsurpassed desire for success, he knows it would take more than luck to fly without wings across the Atlantic and touch down in the world’s celebrated dreamland.

Table OF Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: Silent Agony: A Traumatic Dance with Traditional surgery

CHAPTER 2: A Surgical Ordeal: Off its Wheels

CHAPTER 3: Unfathomable: The Arduous Roadmap to Recovery

CHAPTER 4: A Determined Journey to Manhood: Defying Tradition and Fear

CHAPTER 5: The Secret Quest of the Brave: Unveiling Ancient Rites of Manhood

CHAPTER 6: The Gruesome Rite of Passage: A Desperate Struggle for Survival

CHAPTER 7: The Agony of Becoming a Man

CHAPTER 8: Surviving the Night: A Tale of Ritual, and Pain in the Wilderness

CHAPTER 9: Survival in the Jungle: A Journey into Manhood

CHAPTER 10: Survival Lessons in the Heart of the Wilderness

CHAPTER 11: Fire in the Storm: Lessons in Survival

CHAPTER 12: Surviving the Deadly Marshlands: A Night of Peril and Lessons

CHAPTER 13: Becoming Men: A Journey of Courage, and the Ultimate Test

CHAPTER 14: A Night of Terror: A Desperate Dash for Survival

CHAPTER 15: The Trial of Manhood: A Lesson in Courage and Pride

CHAPTER 16: Rites of Passage: From Childhood Pranks to Manhood Responsibilities

CHAPTER 17: From Boyhood to Manhood: A Journey of Celebration and Responsibility

CHAPTER 18: From Bravado to Reality: A High School Journey

CHAPTER 19: A Humbling Lesson: Failing Forward and Finding Redemption

CHAPTER 20: A Mother’s Unconventional Wisdom: Lessons in Failure and Resilience

CHAPTER 21: From Failure to Redemption: A Journey of Self-Discovery

CHAPTER 22: Heartbreak on a Sunny Day: A Tale of Lost Love and Humiliation

CHAPTER 23: Journey of Self-Discovery: Healing a Broken Heart

CHAPTER 24: Breaking Dawn: A Journey from Heartbreak to Renewal

CHAPTER 25: From Failure to Triumph: A Journey of Redemption and Rebound

CHAPTER 26: Wonders of First Visit to the City

CHAPTER 27: Dreams Beyond Borders: A Journey of Unyielding Determination

CHAPTER 28: Gateway to the Dream: A Bold Pursuit of Opportunity

CHAPTER 29: A Bold Knock on Destiny’s Door: A Tale of Determination

CHAPTER 30: Triumph and Trepidation: The American Dream Beckons

CHAPTER 31: From Fundraiser to Violent Robbery: A Rollercoaster Journey

CHAPTER 32: Journey to America: Triumph Amidst Adversity

CHAPTER 33: Overcoming Superstition: A Harrowing Night Before Departure

CHAPTER 34: A Night of Fear and Fatal Premonitions

CHAPTER 35: Anxieties of the Unknown: A Journey to America

CHAPTER 36: Flying Without Wings: Dreams to American Skies

CHAPTER 37: Dreamful Sleep: The D-Day to the Star Spangled Paradise

SYNOPSIS

About a year after a youngster, Andayi Mushenye, living in Western Kenya, clings to life through a

gruesome uvulectomy and tonsillectomy without anesthesia, he wakes in the wee hours of the night to

discover his brother Rono has disappeared. He hears commotions and, upon waking up, finds his uncles

are counseling him tensely. Since his father died a few years prior, the presence of his uncles in the wee

hours eating chicken, the chicken dish that signifies a big event, is the tip that needs to know something

big is about to happen. Upon inquiry, he discovers his brother is about to be taken for circumcision, a rite

of passage. Unfortunately, he is informed he is too young to endure the bloodletting ritual performed

deep into the ancestral forest.

However, an impatient Andayi cannot wait to become a man. Right before dawn, he escapes home,

barely survives a puff adder attack, gets apprehended, and frogmarched deep into the jungle. He gets

stripped of his childhood clothes and joins the queue, and in no time, he hears his brother’s harrowing

screams. Shaken and naked, he steps over to look and, for the first time, discovers what he is about to

face next: a bloody circumcision without any anesthetic. Despite his pleadings and fierce resistance, he is

tumbled and held to the ground, where he undergoes the gruesome rite. Before the hemorrhaging

stops, Andayi and the cohort are shuffled away to stay in a secluded hut deeper into the forest to face

spine-chilling excursions and dangerous expeditions that will instill the bravery needed to become men.

Led by elders, the cohort starts the healing process by learning hygiene, identifying medicinal plants,

survival skills in the wild, character-building drills, tribal history, expectations, and requirements of

manhood. Barely healed, the group participates in menacing fights, dangerous expeditions, and

spine-chilling excursions in the wild darkness to test their quest for manhood. He barely survives, and

the newest cohort of boys-to-men heads out of the seclusion, singing and dancing wildly into the joyous

welcome of the whole village.

After induction into adulthood with a momentous ceremony of his life, impatient Andayi is ready to

begin his life as a young adult and indulges recklessly. Shortly afterward, he is sent away to Chavakali

Boys High School, a boarding school. However, he becomes a rebel student. He does not study, cajoles

and bullies others, and takes no interest in succeeding at his work.

He and his mother proceed to the principal’s office on the day of his exam results. She is naïve and

believes he has possibly done well. She is crushed by what the principal says. Andayi has failed

spectacularly. But, while his mother is furious, her disappointment is most difficult for Andayi to accept.

She surprises Andayi by telling him that she knows he can do better and succeed in life. In the following

weeks, she travels around to many high schools until she finds one that will allow him to attend and resit

his exams. Eventually, one agrees, the Malava High School.

Andayi is determined to make a better effort at this second chance. But almost immediately, he faces

another setback when he visits his sweetheart, Ketsy, who has passed high school and is in a college

preparatory program. He finds her there, but she rebuffs and dumps him. Crushed, Andayi heads back to

Malava High School. As he journeys throughout the night, he steels himself to use this heartbreak to

drive him forward. At Malava, a high school with meager resources, he studies hard. When his mother

and Andayi proceed to the principal’s office on results day, a beaming principal informs her that her son

has triumphed in his exams. Immensely proud of him, she takes him for a vacation in the capital, Nairobi,

to celebrate. He encounters many wonders he has not experienced or seen, such as traffic lights, ice

cream, a hotel room, mannequins in display windows, huge skyscrapers, and terrifying elevators.

Even after passing the High School exams, Andayi faces another setback. He cannot obtain a university

admission because they only admit the top .5% of academic performers due to the lack of universities.

Feeling betrayed, he takes a teaching job earning forty dollars a month, but Andayi dreams of more.

During the ten-mile daily commute on foot, he develops the idea of going to the United States of

America to attend university. He begins by writing to universities in the United States. The initial

explorations are positive, but he soon faces an impossible financial hurdle. The university requires him to

present evidence to show how he can pay the fees, which will cost thousands of dollars in tuition,

housing, and living expenses.

Still determined as ever, a daring plan comes to him. One of his father’s friends is a wealthy man named

Ibrahim. Andayi effectively sneaks into the mansion, locates Ibrahim’s office, plucks up his courage, and

explains the help he is seeking. His daring action pays off, and Ibrahim provides him with some bank

statements that he can use to apply to the university in the United States. A few weeks later, his scheme

comes to fruition, and he receives a letter of admission to Eastern Michigan University.

But wait, there is another problem. While Andayi believes that he will be able to finance his life in

America when he gets there, he must get there first, and that too will require real money for an air ticket

and first-term tuition; he has none. He reveals his plans to a local politician, and a successful fundraiser is

quickly organized. On the last day in the village and flushed with all that money, nervous Andayi

experiences flashbacks of a violent robbery in the home in the wee hours of the night a few months ago.

But he goes to sleep knowing his uncles, armed with machetes, have camped in the home to ensure no

robbery happens.

After the grandmother’s traditional blessings are finalized, the family heads for Nairobi for Jomo

Kenyatta International Airport. Upon purchasing an air ticket, a banker’s check for tuition, and final

preparations on the last night, ghostlike apprehension clutches Andayi at his throat when it hits him that

his flight to America includes being locked up in a plane and suspended in the sky with nothing beneath

them to catch it if it falls out of the clouds. The fear of getting reduced to ashes in a plane crash inferno

overwhelms him. But he cannot tell his highly superstitious mother, who can call the trip off and order

everyone back to the village to cleanse the lurking evil spirits before flying out. In a few hours, he knows

he has survived the night of prayers, sweats, and worries when the ruckus and rumpus of inner city

traffic awaken him.

At the airport departure lounge, he says a tearful goodbye to his family and friends, especially his

mother. In this touching moment, we learn that Andayi is the youngest of her four children. He is about

to leave his widowed mother alone in an empty nest. Teary and nervous, he gathers the courage when

his flight number is announced, ready to board.

From boarding to arrival, Andayi experiences hilarious technological challenges and cultural

misunderstandings during the flight. Over an eight-hour layover in London, he is too afraid to move

around, lest the plane leaves him and he stays put for eight hours. On the last leg, he has dinner and

whisky, and as he begins to doze off, Andayi remembers the first impressions he had of America he saw

from the open-air movies in the village. Now he is on the final leg; he passes out, wondering how the

star-spangled land would look like when he touches down; little does he know he is about to be knocked

up and down, back–to–back.

FIRST THREE CHAPTERS

CHAPTER 1: Silent Agony: A Traumatic Dance with Traditional surgery

The dissonance of mooing cows, crowing cocks, birds bringing sweet high notes, and people

chatting outside the house ushered in a deceptively bright morning. The commotion woke me,

and I stepped out under a clear, blue sky without knowing what would happen.

Amid the cacophony of different species of chirping birds, my Mama, Khasandi, beckoned me,

“Come and sit here, son.”

I thought nothing of the request and sat down. An old man with an unkempt mustache got up,

flashed his heavy-lidded eyes at me, and stated, “Your mother says the hawks are finishing all

her chickens.”

“But I haven’t seen any?”

Right away, he adopted an accusatory tone. “How could you let that happen?” Before I could

figure out something to say, he asked, “Look up in the sky—what can you see up there?”

“Just a clear blue sky.”

“You don’t see any birds?”

I thought it was the usual mind tricks older men played on young people. “No, I don’t.”

He asked again, “You don’t see the hawk?”

The bird that could sprint on the ground, chasing down a lizard, mouse, or rat, was also a

menace to young chickens. The keen-eyed raptor was patient, soaring in the sky, spying and

biding its time for the right moment to swoop and strike. Before anyone realized it, the agile

hunter with the fearless spirit of a conqueror would drop its wings, dive down with its claws

extended, scoop up a chick, and be gone in a flash.

By the time anyone heard the cries from the mother hen and rushed outside, the hawk would

already be skyrocketing and using its beak to decapitate its struggling catch. The people on the

ground would gaze helplessly, watching loose feathers flying off and falling away as the hawk

plucked them to make room to rip its prey open the moment it arrived in its nest, where it

would enjoy the meal in peace.

I sensed he was teasing my boyhood ability. “You mean you are young but don’t have laser

vision that can protect your chickens?”

His offending comment caused me to want to be the first to spot the predator in the sky that had

made it hard for anyone in our village to rear chickens. Older men in the village often bragged

about their superior ability to take a seat to see what a young man could not see standing. I took

the challenge literally and wanted to turn the tables on him by seeing the bird while I was

seated when he couldn’t see it while standing.

“Keep looking. You might be lucky one day.” I heard him chuckle as he mocked me.

But the high dose of ultraviolet radiation from the sun was making it impossible. My vision

blurred, but determined to see the hawk before he did, I kept squinting and opening my eyes

transitorily. Presently, a few birds appeared in the sky.

He taunted, “Anything yet? Or should I close my eyes to see what you cannot see with your

eyes open?”

When he said that, I trained my entire focus on identifying the hawk among the flock for its

ability to dance in the sky or fly backward. I was so fixated I didn’t see him covertly pull some

sharpened metal pieces containing bits of razor blades—pinned on thin bamboo sticks—and

several copper wires out of his bag.

My eyes started to burn from staring at the sunlight. I looked away and shut them to avoid

further discomfort. It took a little while for the blurry splotch of the sun’s after-image to

disappear. Still, I failed to notice he had removed and positioned his surgical tools right by me.

He stated, “Maybe if you look up with your mouth open wide, you can avoid the light from the

sun and see clearer.”

Thinking it was a Solomonic tactic I didn’t know about, I did, and that was when he expertly

plunged a short, blunt stick into the oral cavity that separated my lower and upper jaw. Before I

realized what had just happened, my mouth became stuck in an open position as his helper

stepped up and swiftly held me on the chair.

The old man peeked into my mouth and confirmed the existence of the long uvula at the back of

my tongue. He momentarily stepped back like an artist, taking a long mental view of what he

was about to create, and then leaned forward to make sure I couldn’t miss what he was about to

reveal.

“I’m going to remove the pesky mass of flesh at the back of your throat.”

Having been caught off guard and still thinking it was a silly prank, I did not detect any

disingenuousness. Instead, I stared at him incomprehensibly, more focused on his unsightly,

dirty yellow teeth than anything else.

He continued, “That long flesh grips your tongue, causing you to stutter.”

While speaking in a peculiar voice, alternating between soprano and shoddy speech, the village

surgeon began to insert a bamboo stick with razors on each side and a teaspoon into my mouth.

That was when I realized he was about to trim my uvula, the sharp tongue-like organ in the

inner roof of the mouth just before the throat. To exacerbate the dire situation, the crude

surgical operation would be performed without anesthesia using non-sterile instruments. That

meant that, unlike a standard surgical procedure in a hospital, there would be no quiet,

sterilized room, no MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) to see how far the uvula had grown to

deserve a cut, and no complicated machines to monitor my vital signs.

Out of reflex, my throat tightened involuntarily, and the surrounding air became strained and

tense. When I resisted, his helper promptly pressed me down and held me to ensure I remained

seated and motionless. I attempted to resist by battling it out, but he held my chest and rear end

down using his steel arms and powerful knees. When I started moving my head from side to

side, he moved swiftly and locked it down, ensuring I couldn’t move an inch in any direction.

His hands felt like iron manacles—all I could move were my toes and fingers. The traditional

practitioner, startled by my intense resistance, stepped back, razor in hand.

As soon as he confirmed I was secured, the man, who I later learned also performed

circumcisions, drainage of abscesses, and tooth extractions, rubbed his hands excitedly like he

was about to get to do what he loved most of all. He moved forward and peered deep into my

throat with narrowing eyes. I felt it constrict to repel him, but it was too late. Knowing what he

was about to do, I could feel my pulse viciously pounding in my neck.

A crooked smile lingered on his lips. He quickly stilled himself and brushed off my muzzled,

wide-eyed protest. The man was so focused that he didn’t even move his eyes. He pushed both

items far inside, but with a limited amount of space in the throat, the traditional surgical tools of

razor and sticks bumped into each other.

The resulting gagging caused reflexive movements of my tongue to get caught up in the mix. I

felt a pang of more dread and took a deep and desperate breath to calm my nerves, but it was a

fruitless undertaking. Rattled to the core, my heart started to beat faster and faster.

Since the uvula exists to help expel any objects that are too large to swallow, when he touched

it, it triggered a gag reflex, which caused a contraction at the back of my throat, meant to thrust

objects forward to prevent choking. But these laryngeal spasms did little to slow him down. The

last thing I saw close to my face was his dirty fingernails, so long they had begun to curl under.

As soon as he reached the destination, he made the first cut. I gasped at the suddenness of the

slit and twitched viciously as a half-strangled scream escaped my lips.

At the second slice, the paralyzing pain spread through my body like hot liquid metal. My

eyelids shut tightly in response, and all my facial muscles contorted instantly. To no avail, I

began to fidget and convulse in a desperate effort to free myself from the muscular hands that

had held my head firmly in place. In no time, the village surgeon began to slice off my uvula

inch by inch, deeper and deeper, as if he worried that if he left a millimeter of it, I might die.

From thereon, each snip led to a toe-curling pain that scorched my windpipe and spread like

wildfire throughout my tormented body. With my tongue feeling the cold spoon, I felt the uvula

drop on the shallow part of the smallmouth shovel he had strategically positioned directly

below it. Immediately, I tasted the saltiness of my blood deep in my throat.

Given that there were no suction pipes to clear the blood and saliva, I choked on the fluids. The

instant I swallowed, it ignited a flare of excruciating pain that caused me to shut my eyes again.

Thinking it was over and I could now rest and start my recovery, he gently massaged my throat,

and I overheard him informing Mama, “His tonsils feel enlarged.” He peered into my

bloodstained mouth for his own second opinion and revealed, “They are reddish, which could

indicate infection and risk more complications.”

I couldn’t move to reposition myself because it felt like the pain had paralyzed my muscles.

Struggling to regain my senses, all I remember is going in and out of semi-consciousness with

the gateway to my stomach still in open position. The excruciating pain underneath my skull

had made my ears feel bunged up, making it difficult for their muffled voices to reach my inner

ears to comprehend what they were up to. Despite the pain, I made a strenuous effort to snap

out of the trance and eavesdrop pointedly. That is when I barely ascertained the village

practitioner, and Mama was haggling over what sounded like the cost of another surgical

operation.

Little did I know this would be another second phase of slicing deeper into my throat.

When I finally understood what was about to happen, the possibility of any comforting

prospect disappeared. The bright morning that promised a new beginning a few minutes ago

was no more when I heard the village surgeon warn Mama, “The tonsils could cause

bedwetting, snoring, difficulty breathing in his sleep, or another infection in his throat. They

must be cut.”

When she didn’t object to the dire diagnosis, I felt a perceptible clinch in my gut, causing my

face to curl into disbelief. The confirmation caused instantaneous fear to sweep over me in vast

waves, and my heart started to pound hard with increasing frequency. This time, I was long

past any tolerance level for any more pain. The incisions I was about to endure were going to be

twice as painful and twice as long because the tonsils in question were a pair of glands made of

fleshy masses on each side at the back of my throat.

As if my realization had sent a telepathic message to Mama, she shot me another sidelong

glance. I started to mumble a prayer because, upon hearing the cost, her mouth curled up

disagreeably. I hoped she was going to change her mind. But that yearning didn’t last long

when I heard him caution Mama tersely, “Or else the tonsils could swell, burst, and kill him.”

That warning statement brought my prayers to naught. My primary protector rolled her eyes

heavenward, and I could smell instant fear and concern boiling in her mind. She lowered her

head and turned to look at me wearily one more time, and I whispered the quickest prayer.

However, her eyebrows rose as a trace of urgent concern crossed her face. Mama shook her

head and rubbed on one side of her dimples as if forcing herself to think of a better plan but

failed. When she focused again, she gave me a look only a mother can pull in a horrible

situation, signaling it was going to be painful, but the alternative could be much worse.

Knowing what was about to come, extreme fear and disbelief were the only emotions that

registered on my face. When she turned back to make eye contact with the village surgeon, her

hand moved in helpless surrender. She gave up bargaining over the price and gave him the

go-ahead to do the tonsillectomy.

The man, who was impatiently waiting and had a forehead coated with sweat despite the

morning chill, nodded. He instantly looked my way, his gaze sweeping by me as if it were a

rescue searchlight. The friendly face that had automatically turned into a smile when he

received the money disappeared. His lips folded, no longer pleasant, just business. His

redder-than-red eyes twitched synchronously, causing him to back up a step, and my gut

clenched in twisted knots. When he stepped forward and leaned his dead face into my mouth,

my heart palpitated raucously, prompting my lips to quiver. Aware that the next step would be

another gruesome slice inside my throat, desperate breath started to come in short bursts. My

constricted chest followed suit, and my heart began to beat so maddeningly that I was scared

my body’s main engine was about to knock itself out.

Although I was imperfectly aware of my surroundings, I don’t remember him washing the

blade he had just used to slice off my uvula a few minutes before. Terrified at this new

harrowing prospect, my body started to shake, and all I remember was him instructing his

helper to hold me in place again. Without delay, his hard-nosed aide forcefully locked me in the

same position that he had me when my uvula was shaved off. Before I could even have some

breathing room from the first cut, he gripped me like a savage anaconda.

When he moved on to the second phase of hacking the tonsils, my jaw jerked involuntarily.

Another brand new burning pain seared the inside of my throat. I automatically gurgled and

struggled to breathe, coughing more blood from the previous cut. I gasped for breath, my

eyelids tightened, and I thought my eyeballs would pop out with a bang. The ripping pain felt

like a bolt of lightning had struck my tormented body from head to toe. I winced frightfully as

absolute torment wreaked a devilish agony. But being held in a fixed position, I could only curl

my fingers and toes so tightly to rein in the torturous procedure.

Everything around me was thrown off balance in the ensuing commotion, ending up in a

star-filled blur. Sweat cropped up on my forehead and dripped into my eyes, further blurring

my vision. From thereon, every snip sent searing pain down my trachea and spread throughout

every nerve in my body. As I desperately breathed in shallow gasps, my imagination held me

captive, and I could swear that hundreds of wasps were stinging my sliced throat.

While he continued trimming both sides, I winced as shards of pain shot down to my ribcage.

My adrenaline surged, my heart followed suit, and started to pound uncontrollably. I twisted,

pushed, pulled, tightened all my body muscles, and screamed through my nose, but the

powerfully built helper, an expert in holding down high-strung patients, didn’t let go even for a

second. The more I pushed and pulled, the more he seemed determined to exert his unyielding

pressure. No matter how I changed positions, nothing moved.

Before I could collapse from the pain and pressure in my head, he brought out the dissected

body parts, then quickly stepped back to leave me free to cough out the blood that was about to

choke me. When I paused after expelling air several times, my throat felt like it had just been

scorched with an acetylene torch. Unable to do anything else, I remained in a trance, totally

knocked out by what I had just experienced. In that deadened moment, the only thing I could

hear was my own low, throaty bubbling noises. It was impossible to see past this moment, so I

stayed mute, listening to the pulse ceaselessly pounding in my ears. When my senses started to

come back, the first thing that crossed my mind was that if I’d known this traditional surgeon

would slice the inside my throat, I would have run as if a tornado was raging at my heels and

put the entire Atlantic Ocean between him and me.

As if he heard what was going through my mind, he returned to get his bag, rummaging for a

small bottle containing medicinal ashes. Using his stretched-out middle finger, with a roughness

I couldn’t have anticipated, he smeared it on the fresh wounds. When he continued to rub, and

the concoction started to get absorbed, the penetrating pain felt as if the village specialist was

scraping the skin off my skull. I gagged for air as another kind of debilitating pain entered every

part of my body, like the shadows of clouds on the ocean.

“That will stop the bleeding and numb the pain,” I barely heard him say when he rubbed again

to ensure it had permeated entirely. When I felt his finger on the desecrated wound the second

time, earthshaking pain flooded my skull and put my head under tremendous compression—I

thought it was about to explode.

When he pulled out the thick stick that held my mouth open, my jaw dropped shut, signaling

my muscles to go limp, and my eyelids drooped and shut. Still, it did not stem the scalding

pain, which took its course to lessen. In real-time, the pain had developed a raw quality that

was beginning to feel like it had no end or limit. Heavy sweat from the adrenaline rush trickled

down my beaten face as labored breathing slowly returned to its normal rhythm. As my eyes

watered freely, all I could do was wait for my strength to return so I could take another breath.

But that was easier said than done because my body gave up on me. Unable to make any sense

of the exceedingly excruciating procedure, I deflated like a punctured balloon and sunk into the

gloomiest trance. The helper who had locked me down pulled me off the seat and gently

positioned me face down to let the bleeding take its natural course.

CHAPTER 2: A Surgical Ordeal: Off its Wheels

The moment he left me lying still, I started to breathe out slowly, desperately wishing and

waiting for the searing pain to ease. It took a protracted interval to subdue the agony before I

could even think of moving a muscle. When the pain gradually diminished to a tolerable level, I

started to doubt if I was really my mother’s son. It was hard to rationalize how a mother could

stand around so casually and let anyone hack her child’s throat in such a crude manner. As my

overworked heart slowed from pounding my breastbone, I quietly considered that as soon I

healed, I would start going around the village, making clandestine inquiries, asking if she was

my real birth mother.

The traditional surgeon finally stepped farther away and lit a homemade cigarette. While

inhaling and letting smoke pour out of his nostrils and mouth at the same time, he continued to

speak to Mama regarding my prognosis. The two walked around me, chatting, untouched by

the pain I was enduring. Even though I was utterly dazed, I could hear him enough to discern a

musky smell of arrogance around the man. The bush doctor who had just sliced the interior of

my throat was already telling Mama there was nothing to it.

With trickles of sweat already running down the sides of his face, he commanded his helper,

“Get me some more water.”

The homemade cigarette was still dangling on one side of his mouth as he washed the tools of

his trade. He never stopped inhaling and exhaling his smoke; an onlooker would have sworn it

was the last cigarette on earth. With every part of him oozing a practiced, confident persona, he

finished his cleaning and came back to instruct me, “The blood in your throat is poisonous;

continue to spit until it stops bleeding.”

Without any anesthetizing medication, like a spray to numb my throat, all I could do was take a

deep breath in a desperate attempt to quell my pain, and that was when he left me with one last

piece of advice.

“The secret to the healing magic of the uvula is lying on your stomach with your head resting on

its cheek correctly.”

His words beat like a war drum in my head—I wanted to attack him so savagely, but I had no

usable strength left. So I lay there, numbed by the pain and wondering what the connection was

between my severed throat and his unsolicited advice.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “Once it heals, you will lose the stammering.”

That was the clearest hint I got as to why he had hacked the inside of my throat. The traditional

surgeon pocketed his tools, received his payment, and was gone as quickly as he had shown up.

Afraid to swallow the blood, I lay there for the next hour with my face down, spitting the blood

until it stopped running.

If I thought it was the end of my unbearable pain, I was wrong. As usual, Mama, not to be

outplayed as the healer of all my misery, showed up after concocting her typical herbs and

gently moved me so that I could lay my head on a makeshift pillow fabricated from dry banana

leaves. With much more care, she lifted my head so I could sit halfway to drink the shockingly

bitter liquid laced with hot peppers, ostensibly to kill germs, and salt to cleanse the wound.

I struggled to open my mouth and tasted the iron-flavored salt in my blood at the back of my

throat. My procreator looked directly into my open mouth while holding it ajar by pressing her

thumb and index finger on my cheeks and squealed in it, “No more stuttering!”

She slowly poured, and I closed my eyes, expecting the worst pain. Indeed, as soon as it passed

the cut and the still-raw injury, my throat burned as if I had gulped an acidic solvent.

Afraid any movement on my part could cause it to bleed more, I held still and closed my eyes to

sleep right there.

When she started to speak to my uncle, and I could hear again, I came to understand that she

believed the elongated tissue under the tongue at the back of the throat that contracted each

time I spoke had interfered with the complex sounds of my speech, and as such needed to be

cut to save me from the social stigma associated with stuttering: a puzzling disorder which

involves voluntary repetition, prolongation along with blocking and other interruptions to the

flow of speech.

She looked at the cut uvula, secured in folded banana leaves, and said, “This is the thing that

has been interfering with his tongue, preventing him from speaking clearly and freely when he

wants to.”

Even though I didn’t want to see the rest of the body parts from my oral cavity, I could not pull

my eyes away from looking at the bloody, pulpy remains of my throat. The revolting sight

couldn’t stop me from taking another look at the remains of my throat that looked like a baby

snail that had been chopped into small pieces.

It was true that my lips or jaw would sometimes tremble as they tried to communicate verbally.

Now and then, when my anxiety was high, I would appear extremely tense or out of breath

when I tried to talk. My mouth would be positioned right, ready to say the word, but virtually

no sound would come out. It was a trait I had inherited from my Uncle Gaka, who was also a

stutterer. Most of the time, the sputtering complications could completely block him from

producing a sound. By the time he regained it, he would, out of frustration, jerk his head and

blink his eyes. However, instead of these bodily movements helping him get his stuck words

out, they would hold and prolong what he was about to articulate. Anyone he was trying to

speak to face to face would have to endure spattering spittle of saliva that would shoot through

his mouth, landing anywhere on their face.

Embarrassed and frustrated as well, he would yell out, “For … for … for … for … forget it!”

Boiled over, you could see his eyes begin to narrow in a fit of rage and bitterness as he turned to

walk away in utter disappointment. But it was not over because his unfortunate human nature

had just denied him the chance to say what he wanted so badly. Immediately after he got hung

up by his halted speech, he would start rattling off indecipherable sounds and making frantic

gestures in all directions. It worsened when he got angry because he couldn’t vocalize his

bottled exasperation to let those who wronged him know how he felt.

“Fo..for..forget it!” was the only remaining easy thing to say so that he could cut everything off

to cool down and hopefully come back to finish what he’d started to articulate. If not, he would

walk away for good.

Most people around him knew he had given up the struggle to verbalize coherently as soon as

he threw his hands in the air, cursed in frustration, and walked away. At times, when he was

lucky to get his tongue to spin and spill the words, he would immediately turn around that

moment, and whoever was present would have to listen to what he had to say because he knew

his tongue would get stuck at any moment.

When this happened, I seemed to be the only one who empathized because I understood how

stuttering impacts the quality of life of individuals with difficulties in overall social behavior

and performance. Therefore, living with a highly stigmatized disability has been a challenge for

both my uncle and me.

Even though deep inside I was happy the cause of this inherited condition that made me have

trouble controlling the flow of my speech was cut off, I struggled to raise my hand to feel the

swelling in my neck. It felt hot, tender, and bulky as if the pain had inflated it. So, I remained

motionless.

In a little while, the late afternoon turned into early evening, and the sunset quickly ushered in

the prelude to nightfall. The last light outside faded quickly, setting me up for the first night of

the most unbearable pain of my life. The tormenting spasms had not let up; they were still

searing through my body, and my amateurish illusion of what I could do to lessen the anguish

took wing. Imagination took over, and I thought if I gently caressed the outside of my throat, its

debilitating severity would start diminishing faster. But that was easier thought than done

because I could barely raise my hand to rub and soothe my swollen neck.

At this incontrovertible instant, I felt cornered and paralyzed, causing my little world to go quiet

and still. In the preceding noiselessness, only pain ruled my body, oozing through every fiber of

my jejune being. In short order, the dark room became apoplectic, like a place out of time where

pain would only leave my body of its own volition. At this tender age, I learned that pain is like

the aggravating or uninvited guest that only leaves at their own leisure.

As if she had realized that with Dad recently passed and gone forever, there was no

better-suited person on the planet to take care of me than her, she stepped into my room quietly

and softly sat beside me. In the dimmed semi-darkness, just by her body language alone, she

could not escape her palpable feelings any more than she could escape her shadow. As such, it

didn’t take me long to make out a feeble glint in a weary eye that I conceivably felt a gleam of

sympathy in her face. Knowing there was nothing she could do to lessen the pain, I concluded

that to restore myself, I was all I needed. So, I pretended to sleep so that she could go to sleep.

The little light in the room made it possible for her to notice I was dozing off. Mama gently

tilted my head back in an elevated position and lifted my chin to ensure my airway remained

open. After a short while, she hoisted the hand-held lantern and blew on the paraffin-lit flame to

turn it off. Right Away, nighttime bathed the lightless room in its own blackness. I wanted to

beg her to leave the only light on, but I knew she wanted the flame off to save the kerosene. She

got up and left the room but did not close my door. When she entered her bedroom, I didn’t

hear her shut and lock the door as she did every day. I suspected she was going to sleep like a

mother of a newborn baby. Even in her deep sleep, she would still be listening to any signs of

things getting worse, ready to get up to meet my physical or emotional needs right away.

In due course, the flame started to burn out the remaining kerosene. Since the room was barely

ventilated, and none of us in the village had ever heard of “deodorized” kerosene that would

reduce the harshness of its vapors, the noxious odor of kerosene instantly filled the room. From

what I know now, an indoor air pollutant that emits poisonous gasses like carbon dioxide,

nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide could kill if inhaled over a prolonged duration. But I was

lucky because the kerosene in its form evaporated quickly, and shortly after, its smell dissipated

because Mama didn’t shut the door all the way.

CHAPTER 3: Unfathomable: The Arduous Roadmap to Recovery

The recovery of my hacked throat was finally on course a few days later. Aside from feeling like

there was something stuck in my throat, I grimaced in pain every time I turned my head a few

inches in either direction. I couldn’t speak or move my neck, and I started to suspect permanent

damage to the vocal cords. Shortly after that, the convulsion of my neck muscles amplified the

pain tenfold when I coughed, swallowed, or sneezed. Mama put me on a restricted liquid diet of

milk, and a few days later, she added soft foods like mashed potatoes, beans, and bananas. Even

though she believed feeding a child is the best way to make them go to sleep, it didn’t make a

difference. On many of these inky nights, even though I closed my eyes, I could hardly

remember falling asleep immediately. It was mostly a futile effort to even try amid the pain and

the harsh smell of lingering kerosene.

From there onward, each time I swallowed, it was like torture heaped on torture in my throat. I

could only close my eyes tight, praying the pain would disappear. In a few days, my tongue

was not only swollen, feeling as if it were too big for my mouth, but also caused a sensation of

fullness in the throat. In the village, there were no lozenges to soothe pain or ice packs on my

throat to help with swelling. The only remedy Mama applied was to soak a rag in warm water

and hold it against my throat for long periods of time to ostensibly speed up the healing

process.

Although saltwater helped clean and promote healing by osmosis, my throat wasn’t healing

well or as fast as we expected. Looking helpless but determined to see me get better, Mama,

eyeing me with restless insomniac eyes from the round-the-clock care she had maintained over

me, resorted to encouragement, “Son, recovery is painful, but it’s just temporary.”

Her words of reassurance didn’t stop further infection. In a few days, the wound started

forming a hard layer of scab. That was just the beginning of my problems because there were no

antibiotics to prevent infection. Soon after, the color of my spit turned blood-tinged, then turned

to green, white, and finally yellow. From the sight of the goo, it was pus, which indicated a

post-surgical complication in the form of septicity. Shortly after that, the ooze from the wound

had accumulated dead neutrophils, which led to a foul odor emanating from my mouth.

Henceforward, every night I tasted the smelly pus in my throat, I struggled to push back a

strong urge to vomit. Since there was no doctor to insert a drainage channel to help evacuate the

discharge rapidly, the only remedy was to continue gargling the peppery, salty water. When

this pungent liquid coursed over the sliced insides of my throat, the eye-popping pain it

triggered was something I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

Instead of consequential post-operative care, the only treatment available is one type of solid

food—dry-roasted corn hard-fried in salt. This change started to complicate my recovery

because the incision wasn’t sutured with stitches that dissolved, which meant the wound hadn’t

closed fast enough. Furthermore, since the throat has no particular bony cage or protection,

swallowing the hard corn and feeling it crudely grating over the raw wound was extremely

tormenting.

With a hacked throat open to trauma, the first time I swallowed the chomped bits, shards of

unfathomable pain excoriated my gullet. Because it hurt every time I chewed, I didn’t grind the

corn enough to turn it into a moistened puree before I swallowed it. But that didn’t make a

difference because no amount of repetitive chewing could have made it possible to swallow

without pain. After a while, the pain settled into a sharp throbbing that felt like someone had

poked inside my barely healed throat with a burning stick.

Since swallowing involves a complex process of many muscles, the cut had altered the lining at

the top of my esophagus. This development meant my throat was also swollen, causing my

airway to narrow. As a result, it was no surprise that tiny particles of the corn got stuck right in

the laceration. Henceforth, the feeling that something was stuck in my throat never left me.

When I complained, I was informed it was the only way the wound could get grated internally

to release more pus, which I was required to spit out. That was not all there was to it. Because of

the roughness of the wound, the dry corn would scrub off and clear the rotting scar tissues

away.

After eating, part of the recovery also required me to gargle saltwater homemade saline to

disinfect and keep the wound clean to augment the healing process for rapid healing. In

addition to my agony, Mama never stopped asking me to take a sip of her usual concoction of

bitterest herbs that she usually hid in the house. No matter how I looked for the nasty dark

liquid mixed with ash in her absence to throw away the potent mixture for good, I couldn’t find

it. My covert plan was to continue throwing the little bottle away until she would give up

storing it in the house. Although I could never find it, it always showed up when I was sick or

misbehaving. Whenever I got into any mischief, she threatened to go and get it. It was so bizarre

how the liquid that possessed all the therapeutic magics could also be used to frighten me into

good behavior.

“If you’re not good, I’ll give it to you,” she would eye me up and caution.

Even stranger, the same threat was also called upon whenever I was sick. She would say, “If you

don’t get better, I’m going to have to give you some of that herbal juice.”

In other words, the stuff was so dreadful it could frighten me into recovery or good behavior.

On the occasions Mama brought it to me, it was so tempting to tell her that the overworked and

underpaid midwife must have given her the wrong baby on the day I was born. In other words,

it was questionable I was her biological son! But my common sense betrayed my tongue because

I wouldn’t have been able to finish the sentence before it got wiped out of my mouth with

African Mama slap that could be just as bad.

When I finally started to heal and walk about, I found Mama sitting where she aired her clean

cooking pots. Although she was scrubbing her cookware with a handful of refined sand, she

looked lost in her musings. The strain in her sleepless eyes was undeniable because she had

been on call throughout the night for many days, ready to offer comfort.

Feeling guilty, I struggled with my speech and asked, “Ma…mama, where did you find the man

that sliced my throat?”

She revealed, “He is not just a man; he is a medicine man with magic powers.”

Angry and in defiance driven by pain, I searched her sleepy eyes for any other explanation, and

when none came, I demanded, “How well do you know him?”

It was an adult question from a young adolescent that she couldn’t duck. My primary caretaker,

whom I had seen catching catnaps during the day, finally shrugged her shoulders and said, “I

don’t know him well, but I saw him cutting the neighbor’s hair.”

Taken aback, I probed further. “How do you know he is a medicine man?”

She replied, “He is known to perform magical treatments.”

Lost for meaning, I looked at her askance, and that was when she reacted as if she had missed a

crucial detail, “When he was cutting hair, the nose of our neighbor started to bleed. He turned

his head upward, and suddenly the bleeding stopped, just like that.”

Such a revelation, coming from a mother who insisted that cutting nails after sunset on a Friday

will keep teeth healthy for a long time—her logic never ceased to amaze me.

After a month, I met the traditional surgeon once again. Although he was shabby, an intriguing

aura of know-it-all surrounded him. The highfalutin, who I suspected used his indifference to

the pain he caused as a badge of his superiority, didn’t strike me as a practitioner who had any

knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the structures in the pharynx.

The flashbacks of the agony he had caused me raced through my mind, and I asked him

bluntly, “How do you prevent your tools from infecting other children?”

He mulled the question over and lowered his voice as if he was about to let me in on a secret of

his life, “I boil them in hot water every evening after all the surgeries.”

His illogical response caused me to demand, “Isn’t that too late after cutting other uvulas and

tonsils all day?”

The egoistic adherent to traditional medicine, whose gray and overgrown eyebrows made him

look like a spooky beaver, quickly discerned my doubts and added, “I also make sure that they

are well-dried to avoid getting rusty.”

Again, his method had no logic, and I stood there looking dumbfounded. He started to walk

away, and when he glanced back, he saw the utter confusion on my face and returned. Standing

beside me, he rested his hands on my shoulders to reassure me.

His bloodshot eyes didn’t hide the mischief beneath them when he smirked without

forethought and raised an eyebrow, “Don’t worry, son, you will be able to have children.”

Even at that young age, I struggled not to conclude he was full of himself. Since a young person

was considered rude and disrespectful for having the nerve to challenge or contradict a lying

elder, I registered my disagreement with a wordless gesture. He was quick to notice, and that is

when he drove his dirty finger with folding long nails into my chest to drive home his point,

“With the stuttering gone, you might even procreate twins.”

Before I could say another word, he left me more confused as I tried to find the connection

between my fertility, uvulectomy, and tonsillectomy. Still angry at him, a rush of anger sent

more blood burning down inside the throat he had sliced. It prompted me to look his way, and

that is when I became more irritated when I saw a pompous spring and careless bounce at the

heels of his worn-out shoes.

By and by, when I was alone, I realized that despite the painful surgical procedures, I was lucky

because, in many other regions, the uvula got sliced off using a red-hot knife, believing that

burning would help sterilize the blade and stop the bleeding. In some other communities, they

tied a nylon string around the uvula and pulled on it daily until it dropped.

What was also eye-opening was that I later found out that there was a belief that to stop a child

from stuttering, one should smack them under the back of their head on a cloudy day. In

particular, I never understood why Mama would slap me on my inion most evenings when I

tried to say something but stammered. She would whack me, and before I could ask why, she

was already going on with her business as if nothing had happened. No wonder there reached a

point where I stayed out of her arm’s reach when evening came, and when I was closer, I

avoided turning my head.

As my everyday life resumed, I had no clue the pain I had endured during the harrowing throat

surgery wasn’t going to be the last of my worst pain; the rudest shock of my life awaited me.

MIDMOST CHAPTER

CHAPTER 17: From Boyhood to Manhood: A Journey of Celebration and Responsibility

Night after night, the skies were ceaselessly bubbling with dazzling stars. We had

successfully survived, and I was now ready to face the real world as a man. Everyone in the

village waited with bated breath for the newest generation that would carry on the blazing

torch of life. Even the woods, which had been so scary on the first night, seemed quietly

vibrating with rapturous adoration.

At midnight, the stars were so bright that I wanted to reach out and grab one of them, but I

chose to sleep and save the energy I would need for the most significant event in a young

man’s life. When I opened my eyes and inhaled, a quick refreshing scent of the forest

ecosystem drifted into my nostrils, ushering in a triumphant feeling that would endure for

many long years.

Early in the morning, when the sky was turned to the pearly gray of dawn, we were

already lined up for our first ravishing haircuts. The painless styling of our hair with

scissors was a step up because, in my previous life as a child, my hair was mowed bald with

a razor blade without regard to any design. I remember when the circumciser, who had

transformed into a barber just for this occasion, snipped around my ear. The sound of the

sharp, close clip made me jump out of the makeshift barber chair. Afraid he might cut my

ear like he’d snipped my DNA distributor, I refused to sit back down. With no time to waste

delaying everyone, my hurried uncles forcefully sat me back down and held my head fixed

in place until the man was done fashioning my nappy hair.

As soon as the sun started to peek through the impenetrable boondocks, beckoning us to

hurry up and greet the grandest event of our lives, we headed for the sacred river to take

consecrated baths. When we finished and started to crisscross the forest pathways back to

the seclusion hut, our appearances glistened with vivid sunniness.

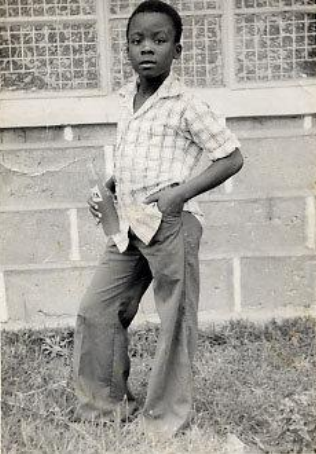

When my brand-new adult clothes were handed over to me, it signaled I was indeed

crossing into my maturated world because I was about to wear zippered trousers and a belt

for the first time. All my life, I had worn oversized shorts with an elastic waistband. When I

put them on, my legs and waist initially felt funny. It took me a few dry runs to learn how

not to get my maleness caught when zipping up my revered bell bottoms.

Although I was over the moon wearing my first long-sleeved shirt, buttoning up the

sleeves became complicated. I was used to an oversized, short-sleeve, three-button shirt

with my name stitched by Mama on the inside of the collar just in case it got stolen from the

clothesline. I spun my wrist backward to get my fingers to button the sleeve on the same

hand but failed miserably. An uncle had to walk me through by showing me how to use the

left hand to button up the sleeve on the right hand and vice versa.

At first, I didn’t recognize the item that was sealed in a small plastic bag until I was

reminded I needed to wear the tiny tight shorts before I put on my trousers. Even after

putting them on and buckling my belt, it didn’t guarantee the expected comfort from my

new interior outfit. My scrotum felt uncomfortable because wearing underwear for the first

time felt funny, pressing onto the center of my manhood.

The minute we were all dressed, we stood like greyhounds in the slips, ready to finally

come out. Rays of sunshine that had struggled to break through the thick forest on many

mornings were forcefully cracking through with full force as if Mother Earth were ushering

in the first full sunlight of our manhood. When we stepped into a more open area for final

preparations, the faces greased with so much Vaseline seemed to be illuminated from

within.

As per custom, we always queued from the first to the last one circumcised. At the end of

the line, the tall, bearded bloke who’d been captured and circumcised by force stood out.

After the final meticulous inspection and with everything in its place, a shimmer of the sun

had turned golden, and it was endlessly streaming through the rest of the ancient trees that

had concealed us from the public for over a month. The imminent crowning moment

caused a sigh of utmost contentment to rise through me—it felt like my Independence Day!

The singing and rhythmic foot pounding began in unison without further ado, and we

headed out. In the distance, I could see the sunlight behind the green hills piled upon each

other’s shoulders. The tribal songs we belted out on this momentous coming-out ceremony

praised warriorhood and encouraged us to achieve it at all costs. The song I remember

chorused, “We shall climb and conquer the mountains of life, just be cautious and patient.”

The closer we got to the outside world, the more the scent of wild roses snuck in with every

breath of the freshest morning air of my life. By the time the thick forest started to thin out,

the new scenery had caused us to confidently march ahead. We were dancing, singing

victory songs, and holding up the indispensable fighting poles that were not only used for

offense and defense in combat but to lever open our way in the bushes in search of food.

Within a few steps, the obliqueness of the forest had waned entirely, and I could see that the

low hills on the forest horizon had worn a haze of inviting blue skies.

At long last, we appeared at the outer part of the forest, and the whole celestial landscape

became instantly suffused with the convivial glow of the risen sun. A sea of exuberant

people who had massed along the route waiting for us detonated with joyful rounds of

applause.

I knew there was no going back when I heard all the praiseful handclaps, songs, drums,

whistles, and uproarious screams. This realization caused me to feel like the earth was also

dancing under my feet in synchronization with my new manly footsteps. These welcoming

sounds finally marked the official end of boyhood and the beginning of manhood. For the

first time in my life, I felt like a hero!

The coming out day was the most anticipated occasion among all mothers, aunts, and

sisters who had missed their sons, nephews, and brothers. I thought Mama was going to be

extremely angry with me. But the moment she saw her only two sons, whom she hadn’t

seen in over a month and wasn’t sure she would ever see alive again, her hurrays went up

an octave.

Our grande dame exploded on her feet and charged toward us like an arrow fired from the

crowd. Her outburst told me she had just let out the breath she had been holding until the

day she got to see her boys back home again, safe and sound.

Everyone understood her uncontrollable hysteria because no one informed any mother of

her son’s death during this man-making sojourn. Worried that disclosing a boy’s death

would upset our ancestors, jinx the rest of the group, or cause a bad omen to the whole

tribe, the elders secretly and hastily buried the weakling late in the night without the benefit

of a casket, prayers, or his mother’s knowledge. It was not until the coming-out day when

she did not see her son, that they revealed the sad news and cleansed the family of the

curse.

Even if the grief-stricken mother wanted to know about the cause of his death, there were

no answers to tell. If her utter anguish threw caution to the side and continued to mourn

and insist endlessly, the elders simply told her, “Your weakling was killed by death.”

End of the story because they could not mention the name of the nonentity or the actual

cause, like drowning, disease, snake bite, hypothermia, lightning strike, bleeding to death,

or any other. They could not point out anything else about the letdown because his evil

spirit would think it was being called back to avenge its death. For this reason, no elder

wanted to be blacklisted by the whole tribe as the one who jinxed the evil spirit to befall his

family or the community.

I was still caught up in the ramifications of these burial rituals and theories when I saw

high-strung Mama trapped but furiously elbowing through the massive crowd. With her

eyes locked on us, she made a quick beeline, got to the tiny space she needed, and

practically sprinted toward my brother and me with tears of utter delight bubbling in her

eyes. When she got to our side, the charming air of vigor and vitality had engrossed her

victorious cheers and rapturous dance.

As she moved closer, I could swear I saw tears of extreme joy finally dropping from her

glittering eyes. Even as the boisterous crowd forcefully jostled for a better view of the

brand-new men, she remained by our side as if she would never ever hand us over to

anyone again. In retrospect, Mama was the perfect picture of the mother hen that doesn’t

leave the nest when she hears her chicks’ first cheeps until they are hatched. She had heard

her boys sing, and now she wasn’t going anywhere until she got them back home safe and

sound.

The instant the jam-packed path opened up, she let out an extended, triumphant

exclamation that I was afraid she was about to run out of oxygen. Caught off guard, my

brother and I looked her way, and by then, she had already gotten a little jiggle room. When

I saw the extreme jubilation in her grateful, ecstatic, and shoulder-breaking traditional

dance, I couldn’t believe it was the same architect of our lives who had sternly castigated

me to shut up and go back to sleep the night I escaped from home. This day was the only

time in our entire lives we saw her celebrating motherhood with seductive and acrobatic

moves by exuberantly twerking her rear end up and down.

Bowled over by the intricate maneuvers of her gluteus maximus and before the ecstatic skit

edged in my mind as the most astounding episode of the day I bid goodbye to my boyhood,

she sang along, quaking her shoulders thunderously.

When I joyfully sang as well, she caught me off guard again. She stopped and expertly

arched her backside until she was bottom up. There and there, she rhythmically twizzled

her nethermost extremities lasciviously. At the sight of her incredibly flawless ability to pull

off such back-to-back erotic mischiefs right before us, I nearly fell over, but our village’s

free-wheeling and ultimate jamboree of the year had to go on.

Her lewd acrobatics were not all there was to the show. In the dancing rainbows of the

bright sunlight, the ecstatic village lassies contending to be our future suitors had thronged

both sides of the road to witness and dance for their potential husbands. The young missies,

dressed to entice and celebrate, were flaunting and shaking every inch of their bodies,

trying to outdo one another to catch our attention. At the sight of their well-executed

sensual finesses, the rapid oxidation of erogenous sensations I had fantasized about during

the month in seclusion rioted through me.

Despite the tumult of pride and delight that had besieged her quintessence, Mama quickly

realized the young girls were also there for the same show but for different reasons. The

morals enforcer, who was adamant we were not allowed to have sex till after we got

married and had children, tactfully hung back to give the euphoric young women room to

dance for their newest boys-to-men group. The excited future brides continuously

crisscrossed ahead of us and circled around, outdoing one another and breezing by us to

touch and feel their covetable studs.

The first time Ankasa touched me, a volcanic eruption of imprisoned passions made me

miss a step, but I quickly recovered. Grinning from ear to ear, she looped a complete circuit

like a lioness scent-marking her territory, tweaking her teenage hips and quaking her

shoulders expertly. Right at that moment, seeing all my attention locked on her, she tugged

on my brand-new long-sleeved shirt for validation, and the thrill of her attention caused my

pounding heart to skip three to four beats.

On this special occasion, the girls didn’t wear underwear because they wanted to celebrate

their fertility and signify their readiness for motherhood at the most opportune time. When

my youthful mind thought of the sensual possibilities that lay ahead, I smiled wide and

danced wildly.

The night before we departed, I followed a few of us who snuck into the woods to dig out a

yellowish root locally known as mukombero (botanically, mondia whitei). The stem is famous

for its eye-popping libido-boosting effects. Caught up in the rhythm of the intimate

moment, I tapped my pocket to make sure the root was still there and smiled widely at her.

She nodded promisingly, romping and jollying just a few inches from me as if she had a

sixth sensual sense.

With perfect timing, she purposely pumped her frolicking hip into my overhauled turbo

engine, and it warmed up right away. Feeling the electrons from the completed circuit, I

responded with a well-timed tap on her quaking backside. She gave off a mellifluous moan

and scrammed off, dancing and celebrating feverishly. A few feet away, with all my

attention locked on her and hers on me, she circled and repeated the entire flirtatious

sequence, which finally triggered another hot and more massive internal combustion. By

the time she whooshed off, leaving my engine revving, Ankasa had summarily etched her

territory.

Thoroughly imbued with a vernal freshness, the frenzied match and dance went into a

higher gear. It was as if my DNA structure had been secretly fused with an ecstatic rhythm

right from conception. We boogied just as much, trying to outdo each other for the girls to

take notice of the best dancer.

Upon Ankasa’s persistent sneaky touch and tuck, my mukombero-powered engine

automatically switched into cruise control mode and stayed there. I couldn’t believe this

part of my adolescent essence was animated and vibrating with a surge of passion I’d never

imagined would resurrect in me, especially after all that gory etching.

The joyousness sparked by our heartthrobs pushed us to step up the game with

unparalleled confidence. Feeling like I was on cloud nine, the most jubilant occasion

resulted in my best, most full of joie de vivre dance ever. The victory songs and dances

confirmed I had earned the title of a man, once and for all. I was no longer a child to be

shoved or pushed around by anyone. People would listen, consider, and respect my

opinion for the first time in my life.

My manhood was confirmed when we finally got home, and, for the first time, Mama gave

me my own bottle of soda: an orange Fanta. Before this day, we’d only seen soda in the

home when Mama was expecting an esteemed visitor. The first sign she expected guests

was when she took out her ceremonial ornamented linens stitched with interwoven patterns

and covered all the living room seats.

When she donned the matching tablecloth on the dining table, and the rest of the

embroidered pieces on the chairs, that part of the house was officially out of bounds for us.

The moment the chinaware that was only meant for visitors finally appeared, we knew the

visitors were just around the corner. From then on, we couldn’t leave home, because we

wanted to see who would come. When the visitors arrived, it was not unusual for sodas and

cakes to appear on the table out of nowhere.

Our graduation from boyhood to manhood was a defining milestone because, in all the

previous years, she had insisted on pouring our soda into two plastic cups. My brother and

I had to share the drink because we were children, not manly enough to qualify for our own

bottle of soda.

On this day, though, sitting on her spotless and distinguished linen for the first time in our

lives, drinking a personal bottle of soda, and chatting with adults—it confirmed the new

long-awaited status. I could feel the mocking echoes of departed boyhood receding with a

quickness I wouldn’t have anticipated when I escaped from home.

The orange-flavored carbonated drink, whose name Fanta is a short form of the word

Fantasie (German for fantasy or imagination), was supposedly specially manufactured and

meant for the recently circumcised to restore the blood we had shed. The praises of the

second drink to be produced by Coca-Cola after their signature Coke weren’t just limited to

my country. In Rwanda, it is referred to as virginal soda, where only virgins drink Fanta as

it’s assumed to be the most innocent and virtuous of all the sodas.

As I clutched onto a full Fanta bottle in my hand for the first time and felt the kiss of the

fabric of my new bell-bottom trousers on my legs that signaled I had become a man, I

stepped outside and insisted that someone take a photo of me. Nobody would dare

challenge me because it was my day, and anything a Fanta-glorious man requested on his

first day of manhood will be given.

The convivial rituals continued until every relative had hosted us. They started with the

immediate family and then a trip every day to the rest of our external kith and kin. For the

next few weeks, we hopped from uncles to aunties to grandparents, covering everyone on

the maternal and paternal sides. Many chickens, the main delicacy of kudos and

appreciation, were stewed and grilled in our honor to signify our cherished new status. The

gratified kinsfolk bequeathed us domesticated animals and other gifts explicitly meant to

set us up for the next phase of life—marriage.

The variety of animals, ranging from goats to sheep, chickens, and ducks, would serve as

my first form of personal wealth. Over the coming years, I was expected to studiously

nurture them until they reproduced enough offspring, then put them up for sale and use

the proceeds to purchase a cow. I would diligently look after it, day and night, till it gave

birth to enough calves to breed and grow into a herd of cattle.

When the time for marriage came, and after confirming that my bride and all sides of our

two families consented to the new union, I would ceremoniously deliver the herd as

thank-you gifts to the parents who had allowed me to marry their daughter and become

part of their family. This revered traditional benefaction, also referred to as a dowry, is

disparaged as “bride-price” in the Western world due to their strict reliance on money-based

gifts.

When I finally settled at home, I was most excited at the prospect of my own itisi, a typical

round hut with a conical grass-thatched roof meant to be the dwelling hut of a young man.

The father of the unmarried man typically constructs it a few years after his son has gone

through this rite of passage and bestows it right after the young man sprouts his first beard.

Having my itisi, commonly known as simba in other tribes, meant I would be free to come

and go as I wished and could have private guests.

Typically, a young man marries while residing in his itisi, and as soon as his family

expands, he builds a bigger home and leaves the homestead. The delayed transition infers

that while his family is young, he needs his parents to guide him as he learns the ropes of

providing, protecting, and caring for his expanding family. By the time the young man

moves out to be on his own for good, he is independent, well-versed, and grounded in what

it takes to be a successful provider, protector, father, and husband.

The coming-out celebration was a shining moment in my lifetime, one I would never

forget—the prime of my life had finally been set in motion. Being a man was not just a

matter of age, strength, or knowledge but also personal maturity and well-grounded

wisdom. Unless there was a life-saving emergency, I could no longer step into the kitchen

or Mama’s bedroom for the rest of my life. I was now permitted to sit among the revered

old men for a chitchat or to offer my advice.

When any of my compatriots, their wives, or their children died, I would be permitted to

join the pallbearers or dig a grave and take part in the final rituals of laying them to rest. If I

heard cries for help late in the village night, I would be expected to get up, arm myself with

a machete, and head in that direction. Since it takes a village to raise a child, I had earned

the right to reprimand any misbehaving, uncircumcised young man in the village. I was

now going to take full responsibility for my life. And gladly, I would no longer wear shorts

meant for boys, only trousers for men.

LAST CHAPTER

CHAPTER 37: Dreamful Sleep: The D-Day of American Misadventures

On another occasion, just before the cinema van came through, a swaggering comrade was

jogging through the village pathways, throwing punches in the air. He stopped by where

we were seated, huffing and puffing.

When he caught his breath, he warned, “None of you better mess with me; I fought

Sylvester Stallone four times.”

“Where did that happen?”

With a face now covered in sweat, he asked, “You mean you didn’t see me in Rocky I, II, III,

and IV?”

“No, I didn’t.”

He exhaled heavily to bolster his assertion.

“You see these two hands.”

He displayed his folded fists and threw two quick jabs and a punch.

“They are also known as hammers. Stallone was so afraid of me that he escaped to America.

Now I have no one to fight but punch the empty space in front of me.”

The inquisitor quizzed, “What will that do for you?”

He wiped his perspiring forehead and looked around as if about to reveal his dirtiest

secret.

“I must not only be in tiptop condition but also keep my muscles loosened so that they

don’t get cramped when I finally execute the punch that will finish Stallone in Rocky V if

that coward ever agrees to another fight. I hope he does because I will punch him so hard

that all his children will be born mentally disturbed. His defeat will finally show America

and the world his previous wins were a fluke just for show!”

He gave us a final look, daring us to say something. None of us said a word. We knew any

contradictory comment to his claim would be the beginning of a fight because he was

champing at the bit, ready to show his boxing skills. Satisfied he was the undisputed top

dog, he departed, jogging, mumbling, and shadowboxing.

On a bright sunny day, the week of the cinema, I walked over to where my neighbor was

sitting with other neighboring boys under the tree, watching over their grazing livestock.

He revealed, “I have a problem.”

“What problem?”

“Every day, Angela Bassett and Jodie Foster fight over me.”

Congratulations were in order, “Wow … That is the best problem a man can have.”

He disagreed boldly, “No, that is not the main problem.”

Now the rest of us wanted to know, and we let our spokesman go for it. “What is the main

problem?”

Looking like a man caught between several women he loved, he divulged, “My mother says

she prefers Whoopi Goldberg—she is more formidable, and with her, no one will mess with

my property or my children when I’m not at home.” He thought hard for a quick second

and asked, “Do you know, after listening to my mother’s logic, I realized a woman like

Whoopi could be that special wife that can cause a dying husband to smile?”

The claim caught us off guard, and we were glad one of us asked, “Why do you say that?”

Recognition dawned on his face. “Because he knows he is leaving behind a strong woman

that will take care of their children, who will turn out to be also strong and protect their

mother and the love of his life in her old age.”

One of us leaned forward, curiosity growing. “So what are you going to do?”

The potential suitor nodded to himself agreeably. “I can marry all of them.”

I finally asked. “How are you going to afford them?”

“I don’t have to pay for anything,” he asserted, his voice calculating.

Now he had me, and I needed to know. “Why not?”

His mouth curved into a knowing smile. “They are independent American women.”

My desire to know went up a notch. “What do you mean by that?”

A slow smile erased the creases between his brows. “They have more than enough money

to afford to pay for everything on their own.”